|

Soup is rarely fatal; it can maim though. Witness a visitor to the Victoria & Albert Museum who found its restaurant’s serving counter unattended. Too famished to wait, he took his life in his hands and, without any training or certification, helped himself to a bowl of soup. Of course, the inevitable happened. A qualified person would have known that rising steam was indicative of the soup being hot. But not this poor chap. Unsure what temperature it was, he did what any rookie would do - he shoved his thumb in it.

This is the 21st Century and we live in Britain (formerly ‘Great’ Britain). Clearly then, this man could in no way be held responsible for the burns he sustained. The V&A was culpable and compensation was due. For the grievous injury occasioned by that hazardous appetiser, a payment of £400 was made. If I’d bothered to contact him for a comment, he would doubtless have declared that “It’s not about the money - it’s about justice. Now shut up and pass me a Margarita - you’re ruining my holiday.”

The culture has always been different on the railway. “You are responsible for your own safety”, I was told on my first PTS course. Yes, you have a COSS (or PICOW as it was then) to set up a safe system, and a competence regime and Standards structure above that. But ultimately, when you set foot on the ballast, you have a duty to yourself and others to act in accordance with the collective wisdom accrued over time and imparted through training. And, for the most part, that’s what happens.

Traditionally gangs were self-reliant entities, moving from site to site and placing their faith in ‘old hands’ who would take custody of the flags. Whilst not perfect, it was simple protection that served the railway well for generations. The coming of health and safety in the 1970s brought a sharper focus on procedural matters; the Nineties ushered in an era of formalised line blockages. These incremental improvements were welcome, adding to the suite of options available to the person in charge. And accident figures fell accordingly. But the foundations remained firm - built on personal responsibility, held together by knowledge and experience.

But those are woolly attributes, no longer fit for purpose. So responsibilities are being devolved and the foundations undermined. In 2002, Rimini took the preparation of safe systems away from COSSs and placed it with the ignorant. Planners’ competence requirements have since been upgraded but the process is still approached largely as a bureaucratic exercise, generating paperwork to cover backsides. As a consequence, COSSs have lost the skills both to develop their own safe systems when needs be and thoroughly check the fitness of those determined by others. The default is to blindly implement whatever is in the pack. And yet the potential implications of this are laid out amongst the findings of inquiry reports - almost every one uncovers planning deficiencies.

Consultants and strategists delude themselves that a reduction in the amount of ‘open line working’ drives improvements in safety performance. In their wisdom - and supported by years of practical experience gazing out of train windows - committees have decided that blocked lines must be preferable to open ones, and safety is now focussed accordingly. There is a simple and attractive logic to this conclusion but, when you consider the full range of factors, it just doesn’t stack up. Inconveniently, incidents (including fatalities) are more likely to occur in possessions, driven by the increased use of plant, the challenging environment and need for enhanced productivity.

For day-to-day maintenance, the safety professional’s Utopian vision has largely been stopped in its tracks by practicality and frontline resistance: there are insufficient timetable windows to accommodate ‘between trains’ blocks and the mechanisms for securing them are too slow and cumbersome. At least, that was the case until recently. But the December 2010 rule changes - specifically the introduction of Handbook 8 (IWA, COSS or PC blocking a line) - have opened up new opportunities, bringing apparent sanctuary for the trackworker but more pressure, responsibility and bureaucracy for the hard-pressed signaller.

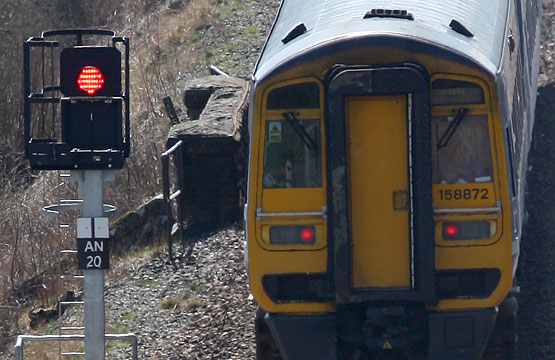

Conceived as a means of quickly inspecting points or getting across a viaduct, T12 (known as a ‘line blockage without additional protection’ today) is becoming the safe system of choice for much of our routine track work - irrespective of its suitability - because it’s quick and involves fewer staff. Gone are the original restrictions over group size (six men) and duration (30 minutes); you can also give up and retake them now to pass a train through. This empowers Network Rail to wave alluring statistics under the ORR’s nose, demonstrating the strides it’s evidently taking to reduce trackworkers’ exposure to risk. But would you feel safe working for hours under signal protection, reliant only on the infallibility of the signaller’s diligence? And how does this transfer of responsibility impact on the wider railway?

|

| But would you feel safe working for hours under signal protection, reliant only on the infallibility of the signaller’s diligence? |

|

Some signallers are busy; others have time for gardening. That’s the nature of our network. More and more though are falling into the former category as the reach of signalling centres extends inexorably. Signaller fatigue is a live issue, also cited in inquiry reports. Combined with planning failures and the sheer volume of line blockages being sought, circumstances are conspiring to erode safety margins.

Procedures are in place to limit the number of blocks a signaller can be expected to handle; in some cases, the figure is calculated by a computer programme. These limits though are not hard and fast - managers can issue an exceedance. How effectively do they take into account the signaller's individual traits and the prevailing circumstances?

When manpower is poised trackside awaiting a line blockage, the pressure to grant it is immense. But poor quality control often burdens signallers with sorting out the mess created by lax planners - incorrect, missing or no protecting signals listed; proposed protection does not [fully] cover the site of work; blockage overlaps another blockage; unsuitable signal types specified. And these are not one-offs - some COSSs come back week after week with the same flawed paperwork and excuses. Lessons don’t get learned.

Yet signallers have been harangued for turning down requests, accused of being uncooperative. Some have been instructed to approve blockages against their professional judgement. The Worksafe Procedure is a managerial trap - more likely to result in supervisory wrath than prevent an unsafe act. The watering down of true competency and an irrational aversion to open lines is imposing ever greater demands on the signaller. As well as controlling his railway, he’s now becoming the trackworker’s first and last line of defence, despite having no understanding of the work being carried out or the unique characteristics of the site. You’re only a reminder appliance away from a close encounter.

For those in touch with reality, the potential for system failure sticks out like a sore thumb; so too does the likely outcome. Why then is it seemingly invisible to the experts in Network Rail and RSSB? Perhaps they choose not to see it for the sake of convenience. After all, the statistics look great!

|